The IT job market is going global, no doubt about it. Working remote for foreign companies or using an occupation overseas as a springboard for relocating is becoming common career trajectories among tech people, and that’s pretty great. However, while we’re rejoicing about the new opportunities, let’s not forget about the growing pains that go hand in hand. One of the most glaring issues international teams run into is that wildly different backgrounds give people wildly different expectations about what employment process, teamwork and professional relationships should look like.

These issues often come up right from the start of job seeking process. When employer and candidate have a cultural divide between them, the communication becomes hindered. And given that initial communication happens in the rigid, standardized form of e-mailed CVs, this can seriously impact the outcome.

The only solution here is to try and bridge gap by getting familiar with other interviewing cultures (and ideally, relaxing the unspoken rules that surround job search somewhat). And that’s where this post you’re reading finally comes in. What we offer is merely some help in the first step of that familiarizing process – assessing the scope of change you’ll need to get used to as you start looking for a job across the border. Many of our team members have tried their luck (with varying degrees of success) with companies located all over the globe, so we decided to pool their observations together and show how basic CV expectations can vary from country to country. This checklist is meant to highlight the problem areas you need to pay attention to as you alter your file for a shiny new overseas employer (we sure hope you do alter it!).

Let’s start with some doomsday talk: candidate filtering by CV is universally believed to be the most soulless and slapdash part of the entire job search pipeline. Different sources cite different allotted times HR managers spend on an average CV before discarding it, but most of them are barely above single digits and utterly depressing to think of, especially if you’re a foreign applicant walking a tightrope of unfamiliar standards and expectations. Still, there is some good news as well. For one thing, pretty much all the world agrees the CV should be short. Two pages seem to be the ubiquitous upper limit, though some countries like Germany, the US or Singapore have a preference for extra condensed, one-page affair. Second, the basic narrative outline remains the same across the world: you state your desired position, give a brief idea of your personal circumstances, zoom in on skills and experience and provide contact info. So, at least there isn’t that much free space to screw up too badly, as long as you stay aware of common pitfalls.

Most of those pitfalls lurk in the depth of specific paragraphs (that we will get to in a short while). But first, there are two larger-scale sources of trouble to address.

Language is probably the most obvious stumbling block for those setting out to test the foreign waters. All that can be said here is that the average employer expects proficiency. At the interviewing stage you can get away with blunders in spoken language – the spontaneity of interaction naturally makes standards slacker, plus there’s an interpersonal element to win you back some points. In printed form, on the other hand, every mistake becomes glaring. However confident you are in your skills, try to run your CV_fin.docx by a native speaker. Simply funding a full translation, on the other hand, is pointless, as the unrealistic expectations will blow up in your face during the first Skype conversation. When in doubt, there’s always an option of switching to English (unless the use of native language is specified in the listing); however, the end result may differ. Typically, the EU countries turn out to be the most receptive to lingua franca. The rest of the world is more of a wildcard.

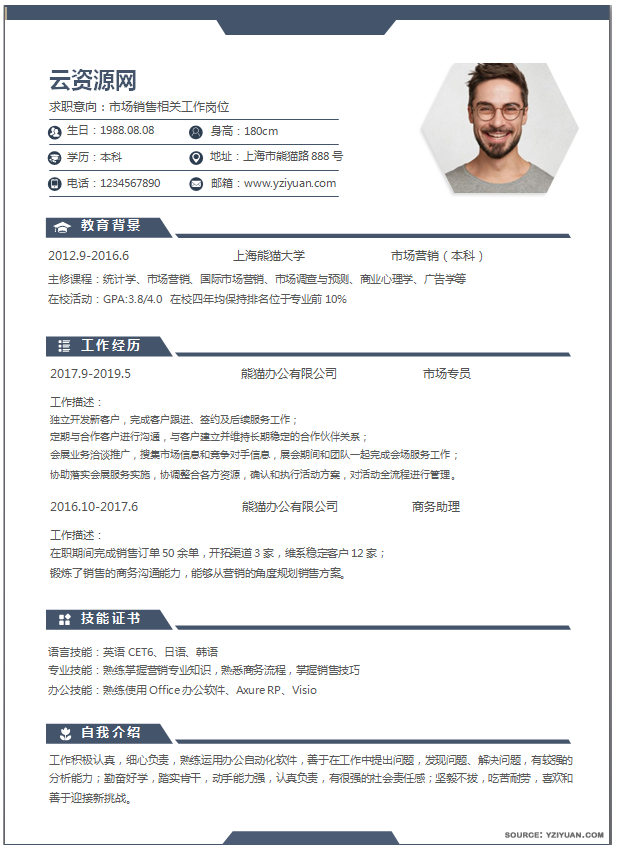

Layout is a more subtle and, consequently, often overlooked factor. The content might be similar wherever you apply, but the typical structure, blocking, details of presentation vary from place to place. Few headhunters are so petty as to consciously ditch you into the reject pile just over that, but plenty can overlook the information because it wasn’t where they expected to see it or just get an ‘off’ feeling from the resume. That’s not the way you’d want to stand out among the candidates, so it’s better to put extra effort towards blending in. For most geographical job search vectors there are templates available online. In case of particularly popular ones, at this point of human history you have an opportunity of delegating broad-strokes editing to software. Lately, the CV constructor market has been trying to branch out in terms of localized formatting, so the apps like CV Master or Intelligent CV – Resume Builder account for layout adjustments, among other things.

CV according to German (on the left) and Chinese (on the right) canons. Take note of the differences in personal profiles

And now let’s go over the specific sections, dissecting the blocks that are widespread enough around the word to be considered universal.

Personal information is an umbrella term for everything that’s not directly connected to performing the actual job: age, gender, family situation, appearance (usually telegraphed via enclosed photo), any fragments of personal history (such as place of birth). The tricky part here is to read the room well enough to volunteer the suitable amount of intel. It’s something of a hot-button CV area, as attitudes regarding how much the future employer needs to know about your baseline self vary dramatically. On the ‘bare minimum’ end of scale there are countries with advanced equality politic, such as the US or UK. In the companies based there most of the positions listed above would be considered sensitive matters that can trigger biases and should be avoided to keep the proceedings irreproachable in the eyes of law. In most European countries, on the other hand, they would come off as overall neutral if kind of redundant. Age and marital status can be included, but nobody would bat an eye if they are not. And then, there are Asian countries where employers are inclined to know all that and more. Japan, for instance, requires detailed information on the candidate’s family makeup for insuring purposes. In China foreigners are subject to scrutiny due to staff retention issues, so anything that hints at settling down in the country is probably worth mentioning.

Job position the candidate is after is one thing they can throw into the header without overthinking – it’s as ubiquitous a part of canon as it gets. Which makes sense, seeing what the whole process is all about.

Contacts are straightforward enough: in descending order of importance, the foreign employer is going to need your e-mail, phone number and address. There have been some disagreement over addresses and how precise they need to be lately, but for now, full address is still perfectly viable. The US has adopted a habit of incorporating the LinkedIn profile hyperlink in the CV, but in other countries social media shortcuts don’t seem to be a common practice.

This basic overview of relevant characteristics typically makes up the ‘header’ (or ‘sidebar’, for more flexible layout variations) of CV and tends towards laconic and compressed in presentation. Now we’re getting to the meatier sections that take up most of the space and do as much convincing as they do informing the employer.

After the personal profile, an introductory paragraph might or might not follow, depending on the local rulebook. Whether it’s supposed to in your specific case is an important question to clarify: omitting it when expected can read as ‘uninvested and impersonal’, adding it out of place can come off as tryhard and breaking the otherwise streamlined structure. As a general rule, the more a given interviewing culture urges the candidate to self-promote and take charge, the more organic an introductory blurb will look in a CV. Compared to other parts’ rigidity, it’s more or less freestyle and acts as a highlight reel of the most outstanding features, be it career achievements, aspirations, skillset or outlook. Basically, it’s your sales pitch – though in some countries the general tone of the text is allowed to betray it more than in others.

The crux of the main CV body, however, is the holy trinity: experience, education, and skills. The order matters. Some traditions go with the chronological order: from academic background to job history. Others put work experience first as the focal point – it’s likely to interest your future boss the most. Sometimes the protocols vary for the beginners who lack experience (they can place emphasis on education for a more winning impression) and everyone else, and that’s an essential, if subtle distinction to be mindful of. ‘Skills’ section more often than not has less prominent placing than job history, coming afterwards.

Job history introduces a list of previous occupations, listed either in chronological or reversed chorological order. For each one a brief description is enclosed that includes the following points:

- Name of the company

- Location (does not always apply)

- Position

- The precise time period of occupation (usually down to month)

- Responsibilities (does not always apply)

- Accomplishments (does not always apply)

Regarding two last points, whether you talk about what exactly you were doing at work and what you have to show for it (and if yes, how detailed you get) depends on two things. First is, again, the general propensity to self-promote on the local job hunting scene. Second is the presence of absence of a different space where you can delve into in, such as occasionally emerging ‘Accomplishments’ section, or a whole separate document, i.e. the US-style cover letter or Shokumu-keirekisho in Japan.

With academic background the range of coverage is even wider. For one thing, different cultures start summarizing from different points, with an eye to peculiarities of the education system in question. In Asia and in some parts of Europe the candidate stating their high school attendance is par for the course, while in, say, Russia that would ring irrelevant and a touch desperate. In the same vein, the appropriate amount of detailed information about tertiary education: majors, noteworthy courses taken, GPA, should be determined on case by case basis. The common minimum normally includes:

- Name of school(s)

- Department/program, etc.

- Years of attendance

- Degrees attained

As for skills, they are largely intuitive, especially in the IT where professional capacity can be pretty easily atomized into a list of technologies and languages. The most prominent hurdle is soft skills. Double check the CV template before you include them alongside field-specific competences: perhaps there’s a better place for them to go (the introductory career summary, self-promotion field, etc.). Incorporating the standard virtues into personalized context can make them sound less trite and resonate better. On technical side, pay attention to the skills you have been certified for (they might need to be moved to a separate unit) and language proficiency (some places have a practice of putting them at the top, with personal info, especially if you’re a foreigner speaking the native language).

At the periphery of relevance and importance, there’s the hobbies/interests section, usually relegated to the humble spot at the bottom of page. Setting out to do the research, we expected it to be more of a culturally dependent point of contention. Yet, to our surprise, there wasn’t all that much correlation between formality levels woven in to the job search culture and attitude towards offering those glimpses of off-hours individuality. Even in the countries that are regarded as very ‘traditional’ in their heightened sense of distance between an employer and an employee (such as Japan), hobby mentions are greenlit nowadays as a means of breaking the ice and fueling small talk.

At the same time, not every CV structure reserves a separate section specifically for whatever you like to do in your spare time. At times it gets fused with other similar topics (such as self-evaluation in the Chinese canon or activities unrelated to the job field, such as volunteering, in the Western European one). In this case, you can and should move hobbies to the backseat if there’s something more meaningful or striking you want to talk about. Small talk doesn’t differentiate.

A word or two remains to be said about recommendations which have become exercise in hypocrisy as of lately. An attitude that seems to be gaining popularity, especially in Western regions, is that you’re supposed to have some under the belt and ready to fire – but avoid mentioning it first. The question of recommendations should be brought up during interviews by the employer, if at all; starting this conversation too early is considered in poor taste. However, not every country has yet ratified this new etiquette rule, so in some places (i.e. Singapore) HR managers still are looking for references in the CV proper. This disparity is important to keep in mind.

And that’s it for the most common and widely familiar parts of an average CV worldwide. The catch is, this list is not exhaustive for every CV template. Many localized variations come with their own additions, some of which we have made offhand mentions of while talking about various points. Here are just a few of them:

- Licenses, certificates, etc.

- Awards, scholarships

- Commute details

- Reasons for application

- Personal requests

‘Extra’ sections are both easier and harder to work with than the standard fare. On one hand, you have less preconceived notions about them, so there’s less temptation to slip into assumptions based on your native experience. On the other, without that shared ground, you have to discover all the unspoken rules and conventions surrounding them from square one. A good example of how unfamiliar additions can trip you up would be the ‘Personal requests’ point from above. It’s a compulsory part of the Japanese CV template where you can specify your needs to the employer. It’s very tough to fill out intuitively without giving them the wrong vibe: a composite structure of etiquette rules regulates which requests can be actually brought up here and what phrasing to use in different cases.

In conclusion, it’d be nice to wrap this post with a list of sources. But, to be honest, most of us agree that you’re going to be better served by googling cv templates for your target country (especially in its respective language) – most universal sources have less depth and detail. The aforementioned software (CV Master, Intelligent CV – Resume Builder, etc.) can help you to get started with general structure for some of job markets. If you want advice on a specific issue, reaching out to big international online communities works well (we owe a lot to /jobs and /IWantOut subreddits, in particular). Good luck!